My mother, God rest her soul, had as many faults and foibles as I do. On the back of a #10 envelope (her, and now my, favorite place to make a note or write a list) she scribbled that she had "a lifelong interest in education." This so that I would remember to put the information in her obituary.

And she made sure that I had an excellent liberal arts education, for which I am grateful every moment of my life. She enrolled me in Catlin Gabel School, a private grade and high school, when I was eleven; she continued to pay my tuition at Reed College even after I got married at the age of twenty; and she paid for me to get a master's degree at Portland State University when I was twenty-eight.

The summer I was fifteen, she had me take a class with her at Reed, Calligraphy, taught by Lloyd J. Reynolds (1902-1978). If you have ever had a great teacher, you know that his or her light stays with you for the rest of your life.

The way Lloyd approached his subject, calligraphy was more than the "study of beautiful writing." It was also the study of people representing their ideas in symbols and letters. So he began teaching us by going through the alphabet. Aleph, our letter A and a, came to us through the Phoenician alphabet from an Egyptian hieroglyph representing an ox's head, the bar on the A representing the ox's horns. And so on.

By the time he got to the letter X and x, he explained that the word Xmas was not a tacky modern abbreviation, like the word nite for night, but that it represented X, the Greek letter Chi, a short form of Christ. Xmas was first used as early as 1100. Even today, though, the word is considered informal, and not appropriate in the best writing.

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Xmas

Labels:

Aleph,

calligraphy,

Chi,

Christ,

liberal arts education,

Lloyd J. Reynolds,

nite,

Reed College,

Xmas

Sunday, November 2, 2014

Bocage

I had a wonderful word in mind for my June 6 post: bocage. This year we marked the 70th anniversary of D-Day on that day, when the Allied armies mounted the greatest invasion in our history to take back the European continent from the Nazis.

According to the Wikipedia entry, bocage is a Norman French and English word typically meaning fields broken up by woodland thickets, which act as both windbreak and boundary. In American English, the word bocage came to mean hedgerow. The soldiers who stormed the beaches and pushed into Normandy encountered heavy resistance both from the enemy and from the very dense bocage.

The day I started working on this post was Hallowe'en, a good day to post about words like Samhain, hallow, or soul cake.

But I could not make myself write about a word or phrase with a Hallowe'en theme. If this is what you are looking for, please let me refer you to the Writer's Almanac, by Garrison Keillor, where you will find an appropriate Hallowe'en entry, as well as other interesting notes about the date, October 31.

I do not know if Garrison Keillor is a dreamer or not, although I imagine that as a writer he must have some characteristics of the dreamer. But the man also has a staff to help write seasonally appropriate entries, even out of season. (Note to self: what would it take for me to do this? More than I have, or not?)

Of course, having a staff also makes the possibility for mistakes even greater. In the Hallowe'en post, he (or, as I imagine, one of his staff) says, "Martin Luther was a monk who disagreed with the Catholic Church's practice of selling indulgences, which forgave the punishment for sins." In fact, the indulgence--that is, the payment you had to make for forgiveness--is the punishment, and, in return for the payment, you got forgiveness. So this should read: ". . . selling indulgences, by which you could have your sins forgiven."

According to the Wikipedia entry, bocage is a Norman French and English word typically meaning fields broken up by woodland thickets, which act as both windbreak and boundary. In American English, the word bocage came to mean hedgerow. The soldiers who stormed the beaches and pushed into Normandy encountered heavy resistance both from the enemy and from the very dense bocage.

The day I started working on this post was Hallowe'en, a good day to post about words like Samhain, hallow, or soul cake.

But I could not make myself write about a word or phrase with a Hallowe'en theme. If this is what you are looking for, please let me refer you to the Writer's Almanac, by Garrison Keillor, where you will find an appropriate Hallowe'en entry, as well as other interesting notes about the date, October 31.

I do not know if Garrison Keillor is a dreamer or not, although I imagine that as a writer he must have some characteristics of the dreamer. But the man also has a staff to help write seasonally appropriate entries, even out of season. (Note to self: what would it take for me to do this? More than I have, or not?)

Of course, having a staff also makes the possibility for mistakes even greater. In the Hallowe'en post, he (or, as I imagine, one of his staff) says, "Martin Luther was a monk who disagreed with the Catholic Church's practice of selling indulgences, which forgave the punishment for sins." In fact, the indulgence--that is, the payment you had to make for forgiveness--is the punishment, and, in return for the payment, you got forgiveness. So this should read: ". . . selling indulgences, by which you could have your sins forgiven."

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Archaeology Best Sellers, In Three Parts

Okay, all right! (Yes, okay should be spelled out, not abbreviated o.k. and all right is two words.)

Once again, you know more about me than I wish you did. Although, along those lines, I have to say that the best writing is, at its heart, honest.

I cannot depend on myself to complete the tasks I've set for myself (to say nothing of the tasks other people might like to set for me). I wrote a post on Connelly's Parthenon Enigma and planned to write two more posts on current archaeology books, Brier's Secret of the Great Pyramid and Cline's 1177 B. C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed.

And, just so we're square, the thesis of Brier's book is a theory developed by French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin, in turn based on his father's insight (his father is also an architect) that the Great Pyramid at Giza was built by means first of an exterior ramp and then an interior ramp.

The thesis of Cline's book is that the migration or invasion of the Sea Peoples, so-called, who probably came from Western Europe, may have brought about the catastrophic collapse of the Late Bronze Age. I read carefully, but did not come away with more information than that.

Why is it, I often wonder, that I am not good at assigning myself posts. And the best, and most flattering, answer is that these posts "come" to me. I have an idea for a post and, at first, the idea is a gift. Then it becomes a possibility--"Oh," I think, "that might work"--and let my thoughts play with the idea. And finally it becomes a demand: "I'm not going to be able to put this idea to rest, or get any rest myself, for that matter, until I write the damn thing."

So now you know.

Once again, you know more about me than I wish you did. Although, along those lines, I have to say that the best writing is, at its heart, honest.

I cannot depend on myself to complete the tasks I've set for myself (to say nothing of the tasks other people might like to set for me). I wrote a post on Connelly's Parthenon Enigma and planned to write two more posts on current archaeology books, Brier's Secret of the Great Pyramid and Cline's 1177 B. C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed.

And, just so we're square, the thesis of Brier's book is a theory developed by French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin, in turn based on his father's insight (his father is also an architect) that the Great Pyramid at Giza was built by means first of an exterior ramp and then an interior ramp.

The thesis of Cline's book is that the migration or invasion of the Sea Peoples, so-called, who probably came from Western Europe, may have brought about the catastrophic collapse of the Late Bronze Age. I read carefully, but did not come away with more information than that.

Why is it, I often wonder, that I am not good at assigning myself posts. And the best, and most flattering, answer is that these posts "come" to me. I have an idea for a post and, at first, the idea is a gift. Then it becomes a possibility--"Oh," I think, "that might work"--and let my thoughts play with the idea. And finally it becomes a demand: "I'm not going to be able to put this idea to rest, or get any rest myself, for that matter, until I write the damn thing."

So now you know.

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Archaeology Best Sellers, In Three Parts. Part 1: Connolly

Every once in a while, I read a popularized archaeology book that catches my eye. Lately, for example, I've made my way through The Parthenon Enigma, by Joan Breton Connolly (New York: Knopf, 2014); The Secret of the Great Pyramid, by Bob Brier (New York: Harper Perennial, 2009); and 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed, by Eric H. Cline (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

And I mean "made my way." Except for the dramatic, thriller-style titles, these books, although well-reasoned, are not well-written. They are scholarly works, complete with heavy words and plodding arguments, dressed up as best sellers.

Maybe these works can get away with looking like--yes, even acting like--best sellers, because their main ideas are so great.

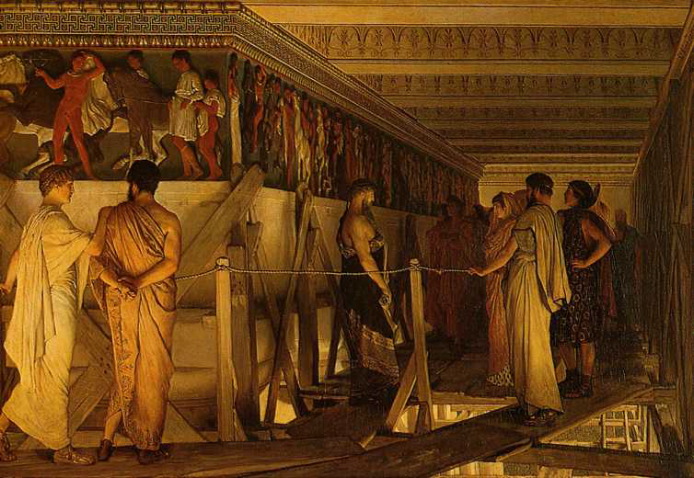

In the Parthenon Enigma, Connolly argues that the Parthenon frieze "tells" the founding myth of Athens, in which Athens's first king, Erechtheus, sacrifices his daughter to save the city. We had lost track, not of the myth itself but of its importance, until we recently recovered a play by Euripides that tells the tale.

Connolly debunks the idea that the frieze shows the procession of the Panathenaea, the great annual festival of the city, which is how we had been used to interpret the frieze.

Connolly debunks the idea that the frieze shows the procession of the Panathenaea, the great annual festival of the city, which is how we had been used to interpret the frieze.

As part of her argument, Connolly depicts all ninety-two marble metopes, or panels carved in bas-relief, from the Parthenon frieze. (In a typical Doric frieze such as this, metopes alternate with triglyphs, carved marble panels with three vertical lines, perhaps memorializing the beam ends of ancient wooden structures.)

The British Museum holds most of the metopes as part of the Elgin Marbles. The new Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum and six other institutions hold the rest.

Connolly remarks that part of the problem in the misinterpretation of the frieze lies with the loss of Euripides's tragedy and part with the diaspora of the marbles themselves. Scholars could have looked at them as a single narrative, but, having to work with the same limitations as the rest of us human beings, they did not.

The British Museum holds most of the metopes as part of the Elgin Marbles. The new Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum and six other institutions hold the rest.

Connolly remarks that part of the problem in the misinterpretation of the frieze lies with the loss of Euripides's tragedy and part with the diaspora of the marbles themselves. Scholars could have looked at them as a single narrative, but, having to work with the same limitations as the rest of us human beings, they did not.

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1868, held by Birmingham Museums And Art Gallery.

Part 2: Brier.

Part 3: Cline.

Part 2: Brier.

Part 3: Cline.

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Return to Casino Royale

In On Her Majesty's Secret Service, James Bond returns to Royale-les-Eaux to visit the grave of Vesper Lynd, a yearly pilgrimage of his. On the road, he and the mysterious, and reckless, Contessa Teresa "Tracy" di Vicenzo race each other in their cars. Later they meet face to face in the casino, where Bond, even though he barely knows her, covers her gambling debt to save her from a dishonorable loss, un coup de deshonneur.

But Tracy is worse than reckless; she is suicidal. The next day, Bond interrupts her while she is trying to kill herself.

Bond finds himself talking alone to Tracy's father, Marc-Ange Draco, head of the Corsican Mafia and holder of the King's Medal for Resistance Fighters (so, even though a criminal, a good guy). Draco convinces Bond to make love to his daughter, to give her hope enough to stay alive, and admonishes him to keep their conversation herkos odonton, which, he says, is Greek for top secret.

Now according to Hank Prunckun, in Counterintelligence Theory and Practice, this Greek saying probably comes from a passage in the Odyssey in which Zeus asks Athena to be careful about letting information slip so easily through the barrier (herkos) of her teeth (odonton).

I am easily amused, and I have been having fun imagining the school boy, Ian Fleming, coming across this phrase and tucking it away in his mind. "Someday," he thinks, "I'll find a use for this wonderful phrase, herkos odonton; I just know I will."

But Tracy is worse than reckless; she is suicidal. The next day, Bond interrupts her while she is trying to kill herself.

Bond finds himself talking alone to Tracy's father, Marc-Ange Draco, head of the Corsican Mafia and holder of the King's Medal for Resistance Fighters (so, even though a criminal, a good guy). Draco convinces Bond to make love to his daughter, to give her hope enough to stay alive, and admonishes him to keep their conversation herkos odonton, which, he says, is Greek for top secret.

Now according to Hank Prunckun, in Counterintelligence Theory and Practice, this Greek saying probably comes from a passage in the Odyssey in which Zeus asks Athena to be careful about letting information slip so easily through the barrier (herkos) of her teeth (odonton).

I am easily amused, and I have been having fun imagining the school boy, Ian Fleming, coming across this phrase and tucking it away in his mind. "Someday," he thinks, "I'll find a use for this wonderful phrase, herkos odonton; I just know I will."

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

Casino Royale

The time has come, I'll wager, for an annotated edition of Casino Royale (first published in London by Jonathan Cape Ltd in 1953).

Case in point:

Bond is at the roulette table. He has lost the money his government bankrolled him so that he could clean out the villain, Le Chiffre. He is despondent, with nowhere to turn. What can he do now?

His American spy friend, Felix Leiter, slips him a new stake, an envelope full of cash, and says, "Marshall Aid. Thirty-two million francs. With the compliments of the USA."

Note:

After the devastation of World War II, Europe struggled to rebuild. The Marshall Plan, named for Secretary of State George Marshall, provided $13 billion in economic grants and loans to the United Kingdom, France, and other European nations, including enemy combatants, Austria, Italy, and West Germany, over a four-year period from 1948 to 1951. The idea was that the slow start of economic regrowth in postwar Europe could make countries vulnerable to Soviet Communism and a little stimulus could help prevent this.

So Felix is joking with Bond. Just as the United States provided economic stimulus to Europe, so Felix helps Bond with the money he needs to beat Le Chiffre.

Case in point:

Bond is at the roulette table. He has lost the money his government bankrolled him so that he could clean out the villain, Le Chiffre. He is despondent, with nowhere to turn. What can he do now?

His American spy friend, Felix Leiter, slips him a new stake, an envelope full of cash, and says, "Marshall Aid. Thirty-two million francs. With the compliments of the USA."

Note:

After the devastation of World War II, Europe struggled to rebuild. The Marshall Plan, named for Secretary of State George Marshall, provided $13 billion in economic grants and loans to the United Kingdom, France, and other European nations, including enemy combatants, Austria, Italy, and West Germany, over a four-year period from 1948 to 1951. The idea was that the slow start of economic regrowth in postwar Europe could make countries vulnerable to Soviet Communism and a little stimulus could help prevent this.

So Felix is joking with Bond. Just as the United States provided economic stimulus to Europe, so Felix helps Bond with the money he needs to beat Le Chiffre.

Labels:

Casino Royale,

Ian Fleming,

James Bond,

Marshall Plan,

postwar Europe,

Vesper Lynd

Monday, July 28, 2014

What Is a Sabretache?

James Bond is in Royale-les-Eaux, a fictional fishing village on the coast of Britanny. Royale-les-Eaux was twice a fashionable health spa, once during the Second Empire and again at the turn of the nineteenth century. Now, in the early 1950s, it is a gambler's paradise, where the worldly can play baccarat and other games of chance at the Casino Royale.

Bond is meeting Mathis, his MI6 contact, over lunch at the Hermitage. Mathis will introduce him to Mlle. Vesper Lynd, the woman who will help him in the operation to bankrupt Le Chiffre.

At this first meeting, the beautiful Lynd wears a grey silk dress with a square neck, tight bodice, and slightly full skirt; her waist is encircled by a black, 3-inch-wide, hand-stitched belt. (The dress is by Dior, as it turns out.) Her shoes are a matching black and her hat, a large "cart-wheel" of gold straw, has a black ribbon. Around her neck, a gold flat-link chain lights up her sun-tanned skin; on her finger, a "broad" topaz ring picks up the gold of the necklace and the straw hat.

Her purse is a black, hand-stitched sabretache, a military pouch once carried by Magyar horsemen of the tenth century; we have examples of these pouches as grave goods. Then called a tarsoly, the pouch was suspended from the belt with the saber and so hung under the saber and to the rider's left side. It was often embellished with a coat of arms or monogram on the front flap.

Hussar cavalry soldiers adopted the tarsoly, in part because their uniforms were so tight that there was no room for pockets, but changed the name: German sabel for saber plus tasche for pocket became sabretache.

British cavalry in the Crimean War (1853-1856) still carried sabretaches. According to the Wikipedia entry, "'undress' versions in plain black patent leather were used on active duty."

So to complete the picture of Miss Lynd, this is how I see her sabretache: it is plain, but shiny, black patent leather like those British cavalrymen used in the Crimea.

Hussar cavalry soldiers adopted the tarsoly, in part because their uniforms were so tight that there was no room for pockets, but changed the name: German sabel for saber plus tasche for pocket became sabretache.

British cavalry in the Crimean War (1853-1856) still carried sabretaches. According to the Wikipedia entry, "'undress' versions in plain black patent leather were used on active duty."

So to complete the picture of Miss Lynd, this is how I see her sabretache: it is plain, but shiny, black patent leather like those British cavalrymen used in the Crimea.

|

| A Hussar officer in full dress, army of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807. His sabretache is emblazoned with the White Eagle of Poland. Painting by Jan Chełmiński, 1913. |

Labels:

Casino Royale,

cavalry,

hussar,

Ian Fleming,

James Bond,

Magyar,

Royale-les-Eaux,

sabretache,

tarsoly,

Vesper Lynd

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Athena's Little Owl

Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom, has protected the city of Athens for 7,000 years, the first settlers having occupied the Acropolis in the Neolithic age. And she always hangs out with her Little Owl (Athene noctua), who prefers to nest in nooks and crannies and has likewise frequented the Acropolis since prehistoric times.

The city-state of Athens minted the first silver owl around 526 BCE, near the end of the Archaic Era. The coin was a tetradrachm, about seventeen grams of silver worth four drachms or about four days' labor.

That's a lot of money. Typically you would spend obols or drachms on everyday items; you would spend any owls you might accumulate on luxuries like jewelry or horses or you might save them.

Unlike earlier coins, Athenian owls had a head and a tail: Athena's head was on the obverse and her companion and emissary, the Little Owl, on the reverse.

Silver bullion for the owls came from Laurium, a village thirty-seven miles to the southwest on the Aegean, where ten thousand or more slaves extracted around a thousand talents a year (with one Attic talent equal to 26 kg or 57 lb). Athens owned the mines and rented out some of the mining rights for a percentage of the production.

At the mint in Athens, in a kind of ancient production line, slaves heated the silver in an oven and molded pieces (or flans) by weight. Other slaves carved dies, from bronze or iron, with the image to be imprinted on the coin in the negative. So, for the owl, the carvers hollowed out Athena's helmeted head, in profile, on the obverse die and the Little Owl in three-quarters view with the head turned full front on the reverse die. And other slaves still struck the coins, one at a time, by "sandwiching" hot flans between dies, hitting them with a mallet, and tossing them into a vat of water to cool.

Now in 483 BCE, seven years after the Greeks had turned back the Persians at Marathon, a rich new lode of silver came to light at Laurium. Herodotus (484 to 425 BCE), whom we used to call the "Father of History" when I was in school, tells the story: Themistocles convinced the Athenians to use the money for defense, to build warships, in case the Persians mounted another invasion.

Which, as it happens, they did, in 480 BCE. Only through the exceptional valor of Leonidas and his Spartan 300 were the Persians delayed, at the Battle of Thermopylae, on their way to destroy Athens. For Xerxes, son of the first invader Darius, was as intent as his father on punishing Athens for its part in inciting rebellion in the Ionic colonies in Asia Minor.

Fortunately, the Athenians had time to prepare for the attack, at least to some extent. One citizen buried his owls and other treasures on the Acropolis, and we did not discover his hoard, in the burn layer dated to this event, until 1886.

So the Athenians went to Salamis and witnessed the sea-battle between the Greeks, in warships paid for with owls, and the Persians. The Greeks won, and Xerxes returned to Persia, leaving one of his generals in charge of the conquest of Greece. That general was beaten at the Battle of Plataea a year later.

The Athenians treated the damage to the Acropolis as a "lest we forget" monument and did not start rebuilding until 447 BCE, when Pericles began his building program that included the Parthenon (constructed under the supervision of Phidias from 447 to 432 BCE) and the new Athenian mint, put up in the Agora in 430 BCE. The new public buildings were paid for with owls.

The city-state of Athens minted the first silver owl around 526 BCE, near the end of the Archaic Era. The coin was a tetradrachm, about seventeen grams of silver worth four drachms or about four days' labor.

That's a lot of money. Typically you would spend obols or drachms on everyday items; you would spend any owls you might accumulate on luxuries like jewelry or horses or you might save them.

Unlike earlier coins, Athenian owls had a head and a tail: Athena's head was on the obverse and her companion and emissary, the Little Owl, on the reverse.

Silver bullion for the owls came from Laurium, a village thirty-seven miles to the southwest on the Aegean, where ten thousand or more slaves extracted around a thousand talents a year (with one Attic talent equal to 26 kg or 57 lb). Athens owned the mines and rented out some of the mining rights for a percentage of the production.

At the mint in Athens, in a kind of ancient production line, slaves heated the silver in an oven and molded pieces (or flans) by weight. Other slaves carved dies, from bronze or iron, with the image to be imprinted on the coin in the negative. So, for the owl, the carvers hollowed out Athena's helmeted head, in profile, on the obverse die and the Little Owl in three-quarters view with the head turned full front on the reverse die. And other slaves still struck the coins, one at a time, by "sandwiching" hot flans between dies, hitting them with a mallet, and tossing them into a vat of water to cool.

Now in 483 BCE, seven years after the Greeks had turned back the Persians at Marathon, a rich new lode of silver came to light at Laurium. Herodotus (484 to 425 BCE), whom we used to call the "Father of History" when I was in school, tells the story: Themistocles convinced the Athenians to use the money for defense, to build warships, in case the Persians mounted another invasion.

Which, as it happens, they did, in 480 BCE. Only through the exceptional valor of Leonidas and his Spartan 300 were the Persians delayed, at the Battle of Thermopylae, on their way to destroy Athens. For Xerxes, son of the first invader Darius, was as intent as his father on punishing Athens for its part in inciting rebellion in the Ionic colonies in Asia Minor.

Fortunately, the Athenians had time to prepare for the attack, at least to some extent. One citizen buried his owls and other treasures on the Acropolis, and we did not discover his hoard, in the burn layer dated to this event, until 1886.

So the Athenians went to Salamis and witnessed the sea-battle between the Greeks, in warships paid for with owls, and the Persians. The Greeks won, and Xerxes returned to Persia, leaving one of his generals in charge of the conquest of Greece. That general was beaten at the Battle of Plataea a year later.

The Athenians treated the damage to the Acropolis as a "lest we forget" monument and did not start rebuilding until 447 BCE, when Pericles began his building program that included the Parthenon (constructed under the supervision of Phidias from 447 to 432 BCE) and the new Athenian mint, put up in the Agora in 430 BCE. The new public buildings were paid for with owls.

Labels:

Acropolis,

Archaic Era,

Athena,

Athene noctua,

Athens,

Battle of Marathon,

coins,

die,

drachms,

heads or tails,

Herodotus,

hoard,

Laurium,

Little Owl,

mint,

obols,

silver

Sunday, July 13, 2014

Trajan's Column

Here at Small Talk, I've been having technical difficulties.

Translation: I determined that the charger for my computer was bad. Discovered that it was just too inconvenient to write a post on my so-called smart phone. Refused to pay $80.00 for a new charger from the computer manufacturer. Ordered a knockoff from China. Received my new charger and discovered that it worked.

Each of these tasks managed to eat up one week of my life.

Translation: I determined that the charger for my computer was bad. Discovered that it was just too inconvenient to write a post on my so-called smart phone. Refused to pay $80.00 for a new charger from the computer manufacturer. Ordered a knockoff from China. Received my new charger and discovered that it worked.

Each of these tasks managed to eat up one week of my life.

During the downtime, I kept notes (on my so-called smart phone) about posts I was planning to write as soon as the technology caught up with me, if such a thing is possible, and especially on a Roman battle formation called the turtle (testudo).

For the testudo, a small group of legionaries raises their shields (scuta in Latin) so that the front and top, sides and back, of the squad are protected from projectiles, with the shields covering it like roof tiles.

So the turtle has two primary purposes. One, it can defend against arrows shot by a company of archers on the battlefield. Two, it can shelter against missiles thrown from the walls of a besieged city while the squad digs under the foundation or otherwise tries to break in.

Although the shields are not too heavy to lift and hold--each shield weighs about twenty-two pounds--the formation is unwieldy, because the men in essence overlap shields and move or stay as a unit. The formation can also prove unsuccessful: if positioned directly under a wall from which heavy objects are being dropped, the men can be summarily wiped out, and we have a record of this having happened.

There is a striking image of Roman legionaries in the testudo formation on Trajan's column during the siege of Sarmisegetusa in the second Dacian war (106 CE). (Sarmisegetusa was in what is now Romania.)

I reckon that this turtle is made up of sixteen shields. So I am going to provide a video, if you will, of this snapshot, based on my research into the Roman army at this time.

The senior chief (decanus) yells, "Form the turtle! (Testudinem facites!).

The other chief and both squads, each composed of seven tent-mates (contubernales), smartly raise their shields.

Other legionaries, probably not the men keeping their shields up, begin hacking at the water pipes that bring water into Sarmisegetusa.

This tactic ultimately brings victory. When the Roman army threatens to torch the city, Sarmisegetusa must surrender.

For the testudo, a small group of legionaries raises their shields (scuta in Latin) so that the front and top, sides and back, of the squad are protected from projectiles, with the shields covering it like roof tiles.

So the turtle has two primary purposes. One, it can defend against arrows shot by a company of archers on the battlefield. Two, it can shelter against missiles thrown from the walls of a besieged city while the squad digs under the foundation or otherwise tries to break in.

Although the shields are not too heavy to lift and hold--each shield weighs about twenty-two pounds--the formation is unwieldy, because the men in essence overlap shields and move or stay as a unit. The formation can also prove unsuccessful: if positioned directly under a wall from which heavy objects are being dropped, the men can be summarily wiped out, and we have a record of this having happened.

There is a striking image of Roman legionaries in the testudo formation on Trajan's column during the siege of Sarmisegetusa in the second Dacian war (106 CE). (Sarmisegetusa was in what is now Romania.)

I reckon that this turtle is made up of sixteen shields. So I am going to provide a video, if you will, of this snapshot, based on my research into the Roman army at this time.

The senior chief (decanus) yells, "Form the turtle! (Testudinem facites!).

The other chief and both squads, each composed of seven tent-mates (contubernales), smartly raise their shields.

Other legionaries, probably not the men keeping their shields up, begin hacking at the water pipes that bring water into Sarmisegetusa.

This tactic ultimately brings victory. When the Roman army threatens to torch the city, Sarmisegetusa must surrender.

|

| The testudo, or turtle, formation, shown on Trajan's column. Cristian Chirita. CC by SA3.0. |

Monday, May 12, 2014

Bookworm

The first time someone called me a bookworm, I was a little girl, but I sensed that the word was pejorative.

The word was coined in 1599 by Ben Jonson in a now all-but-forgotten play called Cynthia's Revels. (Well, not completely forgotten; you can find it online.) The play was first performed in 1600 and published in 1601.

"Heart," remarks Hedon to Anaides about the scholar passing by, "was there ever so prosperous an invention thus unluckily perverted, and spoyl'd by a Whore-son, Book-worm, a Candle-waster?" (Cynthia's Revels, III, ii.)

The hyphen in Book-worm, denoting that two words are being coupled in an unusual way, had been dropped by 1855, when Mrs. Gatty finally used the word to refer not to a reader who was also a dreamer but to the anolium beetle and other pests who feed on tasty parts of books.

Here you will find a painting of a man-after-my-own-heart bookworm by Carl Spitzweg.

In passing, let me remark that the now-defunct hyphen in a compound word like bookworm or email causes editors to rip out their ever-greying hair, to hold the line unbecomingly, or to give way to the new while some measure of grace is still possible.

The word was coined in 1599 by Ben Jonson in a now all-but-forgotten play called Cynthia's Revels. (Well, not completely forgotten; you can find it online.) The play was first performed in 1600 and published in 1601.

"Heart," remarks Hedon to Anaides about the scholar passing by, "was there ever so prosperous an invention thus unluckily perverted, and spoyl'd by a Whore-son, Book-worm, a Candle-waster?" (Cynthia's Revels, III, ii.)

The hyphen in Book-worm, denoting that two words are being coupled in an unusual way, had been dropped by 1855, when Mrs. Gatty finally used the word to refer not to a reader who was also a dreamer but to the anolium beetle and other pests who feed on tasty parts of books.

Here you will find a painting of a man-after-my-own-heart bookworm by Carl Spitzweg.

In passing, let me remark that the now-defunct hyphen in a compound word like bookworm or email causes editors to rip out their ever-greying hair, to hold the line unbecomingly, or to give way to the new while some measure of grace is still possible.

|

| The Bookworm, by Carl Spitzweg, 1850. Held by Museum Georg Schäfer in Schweinfurt, Germany. Uploaded by Iryna Harpy to Wikimedia Commons. |

Labels:

Anaides,

anolium beetle,

Ben Jonson,

bookworm,

Carl Spitzweg,

Cynthia's Revels,

email,

Hedon,

hyphen,

Mrs Gatty

Friday, May 2, 2014

Andy Warhol's Marilyn

Sometimes, when I don't have anything to read, I look up a topic on Wikipedia. The other day, my topic was pop artist Andy Warhol (1928-1987). You can look him up on Wikipedia, just like I did, and research him on the internet. Thanks to technology, you can even listen to some of his interviews. In one of these, in the spirit of Christian love, he said, "I've never met a person I couldn't call a beauty."

I will not rehash the whole thing here, but I have an observation about Warhol concerning the pull between his faith and his interest in fame.

Born Andrej Varhola, Jr., in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Warhol was the third son of Slovakian immigrants. He and his family were devout Byzantine (or Ruthenian) Catholics. This church originated in his parents' homeland, Carpathian Ruthenia, from the ninth century--before the Great Schism (1054)--and so is still in full communion with both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.

As a boy, Warhol and his family went to St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh. After graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (later Carnegie Mellon University) in 1949, he moved to New York City, and his mother joined him at some point. Every Sunday he went to mass at St. Thomas More Church, with his mother until her death in 1972 and then afterwards with his dachshund, Archie. Often he went during the week as well.

Warhol was obsessed with fame, an obsession that began in childhood when he was bedridden, during which time he drew, listened to the radio, and arranged pictures of celebrities around his bed. You could see this interest in celebrities as the other side of religious devotion. Salvation through God? Why not ensure some earthly salvation too, by becoming famous and by concerning oneself with others who are famous. An observer remarked that Warhol chose St. Thomas More as his church because famous people, including the Kennedys, attended.

In the days following Marilyn Monroe's death on August 5, 1962, Warhol decided to immortalize her in his Marilyn Diptych. He chose a publicity still from her first movie, Niagara (made in 1953), and silk-screened acrylic onto canvas: twenty-five images of her face are arranged in a 5x5 grid in color on the left side of the canvas and twenty-five images are arranged in the same kind of grid on the right in black and white. (The finished size of the painting: about 81 by 114 inches, or almost phi, the golden ratio, in tribute to her beauty).

In an optical illusion, the color side of the work seems to come forward and show Marilyn in real life. The black-and-white side of the work seems to recede and show her in the shadows, where a ghost might reside.

In another sort of illusion, the images appear to degrade as they are repeated across the canvas. The artist did not clean the screens of gloppy acrylic residue from one image to the next (although it looks like he did clean them between the color work and the black-and-white). Instead of an icon of beauty, Marilyn becomes a face so familiar with repetition as to become meaningless (or, in a later rendition, to be overlaid with the deaths' head of memento mori, Latin for "remember that you too will die.")

As Julian Schnabel says, “There is something at the bottom of all his work that is absolutely heartbreaking.”

Marilyn Dyptich, Andy Warhol, 1962. Held by the Tate Gallery.

Uploaded by Cmyk, 2009.

I will not rehash the whole thing here, but I have an observation about Warhol concerning the pull between his faith and his interest in fame.

Born Andrej Varhola, Jr., in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Warhol was the third son of Slovakian immigrants. He and his family were devout Byzantine (or Ruthenian) Catholics. This church originated in his parents' homeland, Carpathian Ruthenia, from the ninth century--before the Great Schism (1054)--and so is still in full communion with both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.

As a boy, Warhol and his family went to St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh. After graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (later Carnegie Mellon University) in 1949, he moved to New York City, and his mother joined him at some point. Every Sunday he went to mass at St. Thomas More Church, with his mother until her death in 1972 and then afterwards with his dachshund, Archie. Often he went during the week as well.

Warhol was obsessed with fame, an obsession that began in childhood when he was bedridden, during which time he drew, listened to the radio, and arranged pictures of celebrities around his bed. You could see this interest in celebrities as the other side of religious devotion. Salvation through God? Why not ensure some earthly salvation too, by becoming famous and by concerning oneself with others who are famous. An observer remarked that Warhol chose St. Thomas More as his church because famous people, including the Kennedys, attended.

In an optical illusion, the color side of the work seems to come forward and show Marilyn in real life. The black-and-white side of the work seems to recede and show her in the shadows, where a ghost might reside.

In another sort of illusion, the images appear to degrade as they are repeated across the canvas. The artist did not clean the screens of gloppy acrylic residue from one image to the next (although it looks like he did clean them between the color work and the black-and-white). Instead of an icon of beauty, Marilyn becomes a face so familiar with repetition as to become meaningless (or, in a later rendition, to be overlaid with the deaths' head of memento mori, Latin for "remember that you too will die.")

As Julian Schnabel says, “There is something at the bottom of all his work that is absolutely heartbreaking.”

Uploaded by Cmyk, 2009.

Friday, April 18, 2014

Spring Fever

In case you haven't been able to tell, I am in favor of opening the treasure chest of civilization and taking out and admiring the gold circlets, silver studs, and precious beads cached therein. Even at the risk of turning up a cliché (or two).

Our entire heritage hangs in the balance. Will the digital information age lock away knowledge that we can then unlock at any time, if only we know what to look for? Or will it make green our past, so that new and wonderful things can leaf and blossom from it as they have since its beginning? I don't know.

Consider this most beautiful description of love in the spring.

Song of Solomon, Chapter 2

10 My beloved spoke, and said unto me: 'Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away.

11 For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone;

12 The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing is come, and the voice of the turtle[dove] is heard in our land;

13 The fig-tree putteth forth her green figs, and the vines in blossom give forth their fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

Note that I have emended turtle to turtledove in chapter 2, verse 12. I happen to know that, even though I unfortunately do not read ancient Hebrew, the word for turtle should read turtledove. How do I know this? I cannot remember and have not been able to find out, in a rather summary search of the King James Bible (1611), the Revised Standard Version (1901), the English Standard Version (1971), the Living Bible (also 1971), and the Oxford Annotated Bible (1973), from which I learned so much about textual criticism.

I already know that my next post will (or maybe, given my changeable nature, I should say may) be headed "Spring Training." Which, for the record, I thought of before I knew that Major-League baseball announcer Ernie Harwell (1918-2010) opened the first Detroit Tigers Grapefruit-League game of the season by reciting the Song of Solomon, 2:12. He always said "turtle."

Our entire heritage hangs in the balance. Will the digital information age lock away knowledge that we can then unlock at any time, if only we know what to look for? Or will it make green our past, so that new and wonderful things can leaf and blossom from it as they have since its beginning? I don't know.

Consider this most beautiful description of love in the spring.

Song of Solomon, Chapter 2

10 My beloved spoke, and said unto me: 'Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away.

11 For, lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone;

12 The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing is come, and the voice of the turtle[dove] is heard in our land;

13 The fig-tree putteth forth her green figs, and the vines in blossom give forth their fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

Note that I have emended turtle to turtledove in chapter 2, verse 12. I happen to know that, even though I unfortunately do not read ancient Hebrew, the word for turtle should read turtledove. How do I know this? I cannot remember and have not been able to find out, in a rather summary search of the King James Bible (1611), the Revised Standard Version (1901), the English Standard Version (1971), the Living Bible (also 1971), and the Oxford Annotated Bible (1973), from which I learned so much about textual criticism.

I already know that my next post will (or maybe, given my changeable nature, I should say may) be headed "Spring Training." Which, for the record, I thought of before I knew that Major-League baseball announcer Ernie Harwell (1918-2010) opened the first Detroit Tigers Grapefruit-League game of the season by reciting the Song of Solomon, 2:12. He always said "turtle."

Monday, April 14, 2014

Spring Cleaning

In the opening scene of Kenneth Grahame's Wind in the Willows, the Mole has "been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home."

And I imagine that, ever since we gave up a nomadic life, we, like the Mole, reach a point where we must clear out the last of winter and welcome spring by opening doors and windows and cleaning

"[f]irst with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs . . . ." The Mole even gets out his whitewashing brush to freshen up his walls.

As the Mole cleans, he feels rather than observes "Spring . . . moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing." Grahame captures the heart of the matter: When the seasons turn, winter to spring, summer to fall, the Mole and the rest of us feel uneasy about the change but know that we have our own part in it.

Small wonder, then, that the Mole "suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said 'Bother!' and 'O blow!' and also 'Hang spring-cleaning!' and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat."

The Mole knows, just as we know, that we are happier experiencing spring than doing the spring cleaning. So I'm with him when his snout comes out into the sunlight and he finds himself "rolling in the warm grass of a great meadow."

And I imagine that, ever since we gave up a nomadic life, we, like the Mole, reach a point where we must clear out the last of winter and welcome spring by opening doors and windows and cleaning

"[f]irst with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs . . . ." The Mole even gets out his whitewashing brush to freshen up his walls.

As the Mole cleans, he feels rather than observes "Spring . . . moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing." Grahame captures the heart of the matter: When the seasons turn, winter to spring, summer to fall, the Mole and the rest of us feel uneasy about the change but know that we have our own part in it.

Small wonder, then, that the Mole "suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said 'Bother!' and 'O blow!' and also 'Hang spring-cleaning!' and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat."

The Mole knows, just as we know, that we are happier experiencing spring than doing the spring cleaning. So I'm with him when his snout comes out into the sunlight and he finds himself "rolling in the warm grass of a great meadow."

Labels:

Kenneth Grahame,

Mole,

spring cleaning,

Wind in the Willows

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

Dream Gingerbread

One of my favorite books is Victorian Cakes, by Caroline B. King (Boston: Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1988), a food writer's memoir of her childhood in a well-to-do household in 1880's Chicago.

I can't find my copy of the book right now, but, if memory serves, one of the chapters is entitled, "Dream Gingerbread." According to family lore, one of Caroline's aunts or great-aunts had a dream in which a gingerbread recipe came to her; she rose and baked the cake that very night. The cake was wonderful.

I feel obliged to remark that mine is an elderly memory and does not, in fact, always serve. Lately, I got near the end of a spy thriller when I realized that I had read it before, the first time as a stand-alone and not the fourth in a series.

In any case, please let me give you my recipe for Dream Chocolate Sauce, which came to me a few years ago and is, if I do say so myself, quite wonderful.

Dream Chocolate Sauce

1/2 cup butter, unsalted preferred.

(I can manage to choke down the sauce I made yesterday with salted butter, however.)

12-oz. bag Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Chips.

(Mea culpa. I know my taste in chocolate should be more sophisticated, but I crave the chocolates of my childhood, Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Chips and Hershey's Milk Chocolate with Almonds, henceforth with no apology.)

1/2 cup heavy whipping cream, organic preferred.

In a medium saucepan over warm or very low heat, combine butter and chocolate chips, stirring occasionally until they are melted together. Add the cream and stir in; warm briefly. Serve over ice cream or sneak a spoonful when you are alone in the kitchen.

Hmm. Let's see. I am not a recipe writer, but I would say this makes about a cup and a half of sauce.

Gently rewarm the sauce for each use. You can heat the container of sauce in the microwave for 10 to 30 seconds, for starters, or you can warm it in a saucepan with some water around it over low heat, very slowly.

If you walk away and forget what you are doing, as I often do, you may notice that, when some of the liquid evaporates, the sauce crinkles when it comes into contact with cold ice cream. I haven't fooled around with the ingredients enough yet to make it happen reliably, but that is good too.

I can't find my copy of the book right now, but, if memory serves, one of the chapters is entitled, "Dream Gingerbread." According to family lore, one of Caroline's aunts or great-aunts had a dream in which a gingerbread recipe came to her; she rose and baked the cake that very night. The cake was wonderful.

I feel obliged to remark that mine is an elderly memory and does not, in fact, always serve. Lately, I got near the end of a spy thriller when I realized that I had read it before, the first time as a stand-alone and not the fourth in a series.

In any case, please let me give you my recipe for Dream Chocolate Sauce, which came to me a few years ago and is, if I do say so myself, quite wonderful.

Dream Chocolate Sauce

1/2 cup butter, unsalted preferred.

(I can manage to choke down the sauce I made yesterday with salted butter, however.)

12-oz. bag Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Chips.

(Mea culpa. I know my taste in chocolate should be more sophisticated, but I crave the chocolates of my childhood, Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Chips and Hershey's Milk Chocolate with Almonds, henceforth with no apology.)

1/2 cup heavy whipping cream, organic preferred.

In a medium saucepan over warm or very low heat, combine butter and chocolate chips, stirring occasionally until they are melted together. Add the cream and stir in; warm briefly. Serve over ice cream or sneak a spoonful when you are alone in the kitchen.

Hmm. Let's see. I am not a recipe writer, but I would say this makes about a cup and a half of sauce.

Gently rewarm the sauce for each use. You can heat the container of sauce in the microwave for 10 to 30 seconds, for starters, or you can warm it in a saucepan with some water around it over low heat, very slowly.

If you walk away and forget what you are doing, as I often do, you may notice that, when some of the liquid evaporates, the sauce crinkles when it comes into contact with cold ice cream. I haven't fooled around with the ingredients enough yet to make it happen reliably, but that is good too.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Jacob's Cattle

I have been wrestling with Jacob's angel all night long. (More like weeks, really.)

How can I explain that a folk belief, which we in the twenty-first century know is only partially true, worked to Jacob's advantage? Of course, we know that Jacob has God's favor. But we also find out that, typical of our savvy trickster hero, Jacob makes a plan so he will come out ahead.

Here's the story. In exchange for Leah (whom he marries by Laban's trickery) and then Rachel (whom he loves), Jacob has promised to work seven years for each sister.

During his service, just in case Laban asks Jacob to take his share when they part ways, Jacob practices selective breeding. He makes sure that the strongest sheep and goats breed with each other, in the hope that he will get strong offspring. (True.)

And he makes sure that these sheep and goats gaze upon branches carved with mottled, striped, and spotted patterns during conception, in the hope that, according to an old wives' tale, his flocks will have mottled, striped, and spotted offspring as his own and he can pick them out. (Not true.)

Several years into service, Jacob asks Laban to let him go home. Laban reworks their deal and agrees to give him everything he asks for, all the mottled, striped, and spotted sheep and goats he has hoped to take with him, and to move his camp, all the way not home, but close by.

Now there is a white bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, marked with mottled, striped, and spotted patches of maroon and known by the lovely old name, "Jacob's Cattle." It is the bean used in traditional New England baked beans and is now sold as an "heirloom" seed.

So I was concerned that I could make these ideas all come together, and then: Synchronicity! I was reading a book called The Coat Route (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2013), by Meg Lukens Noonan, about the bespoke tailoring of a luxurious overcoat, and ran into the word "flocculent." Rule Number 1: look up unfamiliar words. Flocculent means "fleecy."

A sign! It was a sign that I should write this post straightaway and an assurance that I could, in some small way, pull it off. Call it superstition or synchronicity, we still want to impose an order on the not-so-orderly.

How can I explain that a folk belief, which we in the twenty-first century know is only partially true, worked to Jacob's advantage? Of course, we know that Jacob has God's favor. But we also find out that, typical of our savvy trickster hero, Jacob makes a plan so he will come out ahead.

Here's the story. In exchange for Leah (whom he marries by Laban's trickery) and then Rachel (whom he loves), Jacob has promised to work seven years for each sister.

During his service, just in case Laban asks Jacob to take his share when they part ways, Jacob practices selective breeding. He makes sure that the strongest sheep and goats breed with each other, in the hope that he will get strong offspring. (True.)

And he makes sure that these sheep and goats gaze upon branches carved with mottled, striped, and spotted patterns during conception, in the hope that, according to an old wives' tale, his flocks will have mottled, striped, and spotted offspring as his own and he can pick them out. (Not true.)

Several years into service, Jacob asks Laban to let him go home. Laban reworks their deal and agrees to give him everything he asks for, all the mottled, striped, and spotted sheep and goats he has hoped to take with him, and to move his camp, all the way not home, but close by.

Now there is a white bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, marked with mottled, striped, and spotted patches of maroon and known by the lovely old name, "Jacob's Cattle." It is the bean used in traditional New England baked beans and is now sold as an "heirloom" seed.

So I was concerned that I could make these ideas all come together, and then: Synchronicity! I was reading a book called The Coat Route (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2013), by Meg Lukens Noonan, about the bespoke tailoring of a luxurious overcoat, and ran into the word "flocculent." Rule Number 1: look up unfamiliar words. Flocculent means "fleecy."

A sign! It was a sign that I should write this post straightaway and an assurance that I could, in some small way, pull it off. Call it superstition or synchronicity, we still want to impose an order on the not-so-orderly.

Labels:

Coat Route,

flocculent,

Genesis,

goats,

God,

Jacob,

Jacob's Cattle bean,

Laban,

Leah,

Megan Lucas Noonan,

Rachel,

selective breeding,

sheep

Wednesday, January 29, 2014

Triage

The word triage comes to us from the French trier, meaning to sort or cull, originally used by eighteenth-century French merchants in sorting wool or coffee for quality. So triage coffee is the heap of broken beans you are left with after sorting out the good beans and the best beans.

Dr. Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842) first used triage in a medical sense as surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon's armies from 1797 to the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The great doctor sorted battlefield casualties into three groups: 1) patients who would probably die, no matter what; 2) patients who would most likely live, no matter what; 3) patients who would survive with immediate treatment, but would not survive without.

And, using the model of artillery carriages, drawn by two- or four-horse teams, that "flew" over the battlefield into position, Dr. Larrey came up with flying ambulances, ambulances volantes. The crew of the flying ambulances administered first aid to the wounded and then rushed them to nearby surgical waystations, the forerunners of MASH units, for emergency treatment.

In World War I, English and American medical personnel heard the French using triage for this effective method of saving badly wounded soldiers and so, thanks to the wonderful flexibility of the English language, it became our word as well.

Dr. Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842) first used triage in a medical sense as surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon's armies from 1797 to the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The great doctor sorted battlefield casualties into three groups: 1) patients who would probably die, no matter what; 2) patients who would most likely live, no matter what; 3) patients who would survive with immediate treatment, but would not survive without.

And, using the model of artillery carriages, drawn by two- or four-horse teams, that "flew" over the battlefield into position, Dr. Larrey came up with flying ambulances, ambulances volantes. The crew of the flying ambulances administered first aid to the wounded and then rushed them to nearby surgical waystations, the forerunners of MASH units, for emergency treatment.

In World War I, English and American medical personnel heard the French using triage for this effective method of saving badly wounded soldiers and so, thanks to the wonderful flexibility of the English language, it became our word as well.

Wounded men by the side of the road, Battle of Passchendaele.

Frank Hurley - State Library of New South Wales file:a479035.

Monday, January 20, 2014

Buffalo Bill

Buffalo Bill, also known as William Frederick Cody (1846-1917), won his nickname in a bet against William Averill Comstock (1842-1868) in the spring of 1868. At the time, Cody was a Civil War veteran, civilian scout for the Third Cavalry Regiment, and contract buffalo hunter for the crew laying track for the Union Pacific Railway in Kansas. Comstock was also a Civil War veteran, great-grandnephew of novelist James Fenimore Cooper, and chief of scouts and interpreter for Custer's Seventh Cavalry, the regiment stationed at nearby Fort Wallace.

The officers at Fort Wallace put up $500.00, wagering that Comstock could kill more buffalo on horseback in one day's time than Cody could.

On the day of the bet, the officers arranged for an excursion train to travel from St. Louis to the end of the track at Monument. Cody's wife Louisa and baby daughter Arta were on board with the rest of the audience. The officers provided champagne and lunch for contestants, bettors, and spectators.

Cody rode out on his horse Brigham and shot his favorite Springfield Model 1863. The rifle, which he named Lucretia Borgia after a popular Victor Hugo--and Renaissance--villainess, was possibly the one he was issued in the Civil War. Cody had had the rifle factory-upgraded to breech-load and fire .50-.70 cartridges. Comstock rode I-do-not-know-which-horse and used his 16-shot Henry rifle.

The hunt started at 8:00 a.m. and ended around 4:00 p.m, with Cody the winner. He shot 68 or 69 buffalo (reports vary) to Comstock's 48. Buffalo Bill describes the event most vividly in his autobiography.

Comstock already had a cool nickname, Medicine Bill, so he was stuck with that. He had earned this nickname several years earlier when he had saved the life of a Sioux woman with a deadly rattlesnake bite on her finger. He bit the finger clean off.

We get the word buffalo from Greek boubalos, originally a kind of African antelope. The word came into English through Latin, maybe Portuguese, and Middle French, by 1580.

The officers at Fort Wallace put up $500.00, wagering that Comstock could kill more buffalo on horseback in one day's time than Cody could.

On the day of the bet, the officers arranged for an excursion train to travel from St. Louis to the end of the track at Monument. Cody's wife Louisa and baby daughter Arta were on board with the rest of the audience. The officers provided champagne and lunch for contestants, bettors, and spectators.

Cody rode out on his horse Brigham and shot his favorite Springfield Model 1863. The rifle, which he named Lucretia Borgia after a popular Victor Hugo--and Renaissance--villainess, was possibly the one he was issued in the Civil War. Cody had had the rifle factory-upgraded to breech-load and fire .50-.70 cartridges. Comstock rode I-do-not-know-which-horse and used his 16-shot Henry rifle.

The hunt started at 8:00 a.m. and ended around 4:00 p.m, with Cody the winner. He shot 68 or 69 buffalo (reports vary) to Comstock's 48. Buffalo Bill describes the event most vividly in his autobiography.

Comstock already had a cool nickname, Medicine Bill, so he was stuck with that. He had earned this nickname several years earlier when he had saved the life of a Sioux woman with a deadly rattlesnake bite on her finger. He bit the finger clean off.

We get the word buffalo from Greek boubalos, originally a kind of African antelope. The word came into English through Latin, maybe Portuguese, and Middle French, by 1580.

|

| William Frederick Cody, "Buffalo Bill." United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3a21252. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)