And I mean "made my way." Except for the dramatic, thriller-style titles, these books, although well-reasoned, are not well-written. They are scholarly works, complete with heavy words and plodding arguments, dressed up as best sellers.

Maybe these works can get away with looking like--yes, even acting like--best sellers, because their main ideas are so great.

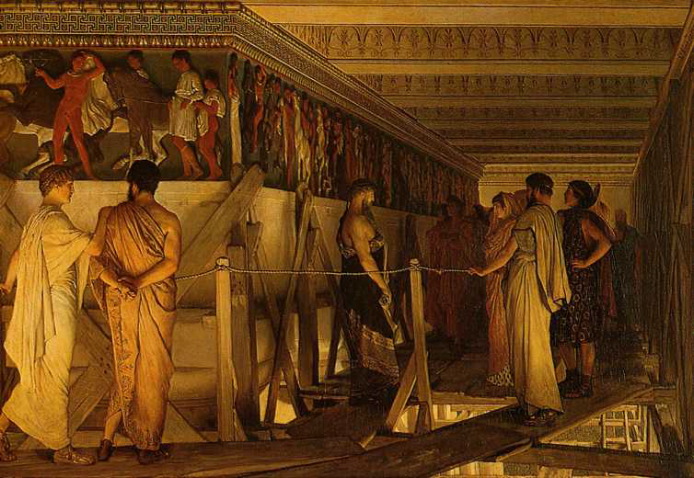

In the Parthenon Enigma, Connolly argues that the Parthenon frieze "tells" the founding myth of Athens, in which Athens's first king, Erechtheus, sacrifices his daughter to save the city. We had lost track, not of the myth itself but of its importance, until we recently recovered a play by Euripides that tells the tale.

Connolly debunks the idea that the frieze shows the procession of the Panathenaea, the great annual festival of the city, which is how we had been used to interpret the frieze.

Connolly debunks the idea that the frieze shows the procession of the Panathenaea, the great annual festival of the city, which is how we had been used to interpret the frieze.

As part of her argument, Connolly depicts all ninety-two marble metopes, or panels carved in bas-relief, from the Parthenon frieze. (In a typical Doric frieze such as this, metopes alternate with triglyphs, carved marble panels with three vertical lines, perhaps memorializing the beam ends of ancient wooden structures.)

The British Museum holds most of the metopes as part of the Elgin Marbles. The new Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum and six other institutions hold the rest.

Connolly remarks that part of the problem in the misinterpretation of the frieze lies with the loss of Euripides's tragedy and part with the diaspora of the marbles themselves. Scholars could have looked at them as a single narrative, but, having to work with the same limitations as the rest of us human beings, they did not.

The British Museum holds most of the metopes as part of the Elgin Marbles. The new Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum and six other institutions hold the rest.

Connolly remarks that part of the problem in the misinterpretation of the frieze lies with the loss of Euripides's tragedy and part with the diaspora of the marbles themselves. Scholars could have looked at them as a single narrative, but, having to work with the same limitations as the rest of us human beings, they did not.

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1868, held by Birmingham Museums And Art Gallery.

Part 2: Brier.

Part 3: Cline.

Part 2: Brier.

Part 3: Cline.

No comments:

Post a Comment